Krishna waters – IV

The Centre’s gazette notifications on July 15 Jal Sakti Ministry taking over the Rivers raise several Constitutional questions. First of all, it violates the Article 14 as two states are treated differently from other states where interstate rivers are flowing. Secondly, it violates the federal nature of the distribution of powers between the Centre and States. The water is the state’s subject. But Centre misinterpreted its common jurisdiction in Concurrent List and provisions of AP Reorganization Act 2014, which nowhere stated that Centre could take away the rivers. Even under general principles of sharing sovereignty between States and the Centre, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are entitled to autonomy in managing the water. This federal principle is watered down as the Centre took over the Krishna and Godavari rivers from the Telugu riparian states. It is arbitrary and atrocious to steal the rivers like this, to say the least.

Also read: River Management Boards

India has as many as 25 major river basins with 103 sub basins, but each is prone to several interstate river water distributes. These rivers are in fact great assets for our economy, agriculture and food security besides development of civilisation on the banks of the rivers. Most of the times the political rulers are interested in exploiting the resources rather than taking measures to protect rivers and ecosystem. Historically and constitutionally we are yet to create a working system of river water sharing disputes or inculcate cooperative resolution of resource distribution related issues.

While we handed over all sovereign powers to British rulers during pre-Independence period, we continued with those half-hearted measures under the highly centralized union. It was Delhi’s paramountcy that made the princely states and provinces totally subordinate to Secretary of State, whose orders were final and absolutely binding on states. Government of India Acts of 1919 and 1935 empowered Secretary of State to decide on water utilisation without leaving any authority or autonomy to provinces. Autonomy was confined to irrigation only under the 1919 Act as Item Number 7 Part 2 of Schedule 1.

Also read: The Constitutional Necessity of Separation

Constitutional power sharing

Under our own Constitution adopted after Independence, legislative powers are distributed between the Union and the States. The use of words ‘water’ in Entry 17 of List II and ‘interstate rivers’ in Entry 56 of List I distinguishes the powers without much elaboration.

Our Constitution in Article 262(1) empowered Parliament to adopt legislation for the settlement of disputes or complaints concerning the use, distribution or control of transboundary waters in a river or river valley. Article 262(2) says Parliament may impede the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court or of any other court in relation to the dispute/appeal referred to in Article 262 (1).

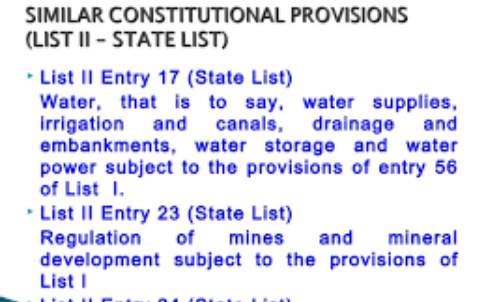

Entry 17 of List II (States List): Water, that is to say, water supplies, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, water storage and water power subject to the provisions of Entry 56 of List I.

Entry 56 of List I (Union List) under Seventh Schedule of the Constitution: Regulation and development of inter-State rivers and river valleys to the extent to which such regulation and development under the control of the Union is declared by Parliament by law to be expedient in the public interest. The distribution of legislative powers through three lists also the distribution of executive powers. A state has executive power on which the legislative power is given in the Lists.

State List simply mentions water, which means surface water within the geographical boundaries of state. States can legislate and use executive powers to utilise the water, regardless of whether the source of the river or its tributary is located outside its boundary or the river draining into another state or ocean. However, this state power is also subject to power of the Union’s understanding of what is better for nation.

Union’s role

In this regard the role of Union is crucial which is reinforced by Entry 20 (economic and social planning) of the Concurrent List. This provision requires states to obtain environmental clearances from the Centre in projects involving major and medium irrigation, hydropower etc., for their inclusion in the national plan. Thus, even without formal legislation, the Union government has the power to exercise significant control.

At the same time, the Parliament can make law and formulate mechanisms to regulate interstate rivers. States got the authority to devise means to utilisation of water supply, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, besides water power and storage as per Entry 17 of States List. Most important rider is that the state powers are specifically made subject to Centre’s power under Entry 56 of List I. The ambiguity in the origin of power distribution is potential enough to create issues in water distribution.

Also read: CJI’s worthy solution to Water Dispute

(The author is Dean, Professor of Law at Mahendra University, Hyderabad, and former Central Information Commissioner)