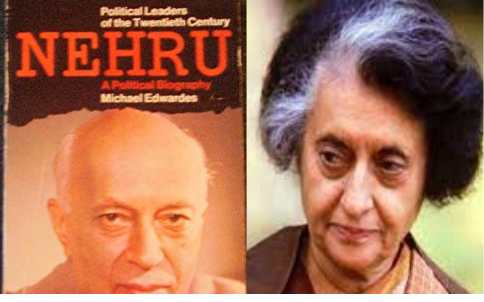

November 14 was birth anniversary of first Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru. November 19 is the day, yet another strong Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi was born. Mrs Indira Gandhi’s Government had banned the book of Biography of Nehru. Why and how it happened?

The import of Biography of Nehru written by Michael Edwards is prohibited absolutely for misinterpretation and factual errors. The M.F. (D.R.&I.) Notification No.102-Cus., dated 13th December, 1975 says: Every copy of the book entitled “Political Leaders of the Twentieth Century-Nehru-A Political Biography” by Michael Edwards (first published by Allen Lane the Penguin Press, 1971, published in Pelican Books, 1973, and made and printed in Great Britain by Coz & Wyman Ltd., London, Reading and Fakenhan set in Monotype Times), including any extract there from, and any reprint or translation thereof, and any document reproducing any matter contained therein.

Factual errors

Some of the books were prohibited for showing India in poor light and misrepresentation. The ground of factual errors was cited as reason for banning Desmond Steward’s Early Islam and Michael Edwards Nehru: A Political Biography in 1975. The government considered that these books were containing grievous factual errors.

During the Emergency, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi took it very seriously and decided to ban the British historian Michael Edwards’ book of biography of her father, Jawaharlal Nehru. It was criticised as overreaction and that ban favoured the book by fetching undeserved publicity. This book was already criticised by critics across the world. Reviewer Manu S Pillai (in Livemint) mentioned the opinion of one scholar who said that this book was guilty of the “worst sort of reductionism” while another found it full of “questionable statements”, and a third challenged the writer’s claim that it was based on 25 years of research. Pillai wrote: “Indeed, “emotional” is a word that appears a great deal in this biography. His flirtation with theosophy was emotional; his sense of identification with India’s peasants was emotional; his desire for the unity of the Congress party was emotional; his socialism was emotional; elections were “an emotional release after the drama of independence”; and even his five-year plans were emotional. In sum, Nehru was nothing but overrated emotion”. He felt it does not deserve ban. He also noted that there were “casual, sweeping claims, such as the suggestion that the first post-1947 election “was essentially a travesty of democracy”, or that the massacre by General Dyer at Jallianwala Bagh was because he “panicked”. Pillai said that ‘the book’s greatest flaw in painting Nehru as a witless shuttlecock between an “essentially communal” Gandhi and a Patel-led capitalist lobby is that Nehru’s own urbane, progressive vision is eclipsed deliberately’. He also wrote that while Patel is correctly lauded as the “true founder of the Indian state”, Edwardes forgets that Nehru was the founder of modern Indian democracy—India’s dawn depended on both. He plays down, for instance, Nehru’s 1931 Karachi resolution as a sop to his ideals—in fact, this document on “Fundamental Rights and Economic and Social Changes” asserted principles enshrined now in our Constitution. Nehru was not enough of a politician, Edwardes complains, perhaps oblivious that it was precisely this quality that made him special to millions ofpeople.

Nehru, an accident of history?

Pillai further wrote: “To Edwardes, Nehru was an accident of history—the wrong man at the right place—rather than someone who earned his stripes. The author arrived at this conclusion and produced over 300 pages detailing it, without access to even one of Nehru’s vast collection of private and official papers. Nehru himself might merely have laughed at the provocation. After all, in 1937, he wrote an anonymous article criticizing himself to encourage his people to hold their leaders accountable.”

Pillai opposed banning of the book saying: “Questions, he knew, must be asked of all tall leaders, but perhaps out of personal affection, or on account of a thin skin, Nehru’s daughter does not seem to have agreed with this principle. So, she banned what was a poorly argued book, denying it its natural demise, and granting it a place of honour among those who resented Nehru then and fear his memory even today”.